Author: Jonathan Swift

Author: Jonathan Swift

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Commentary

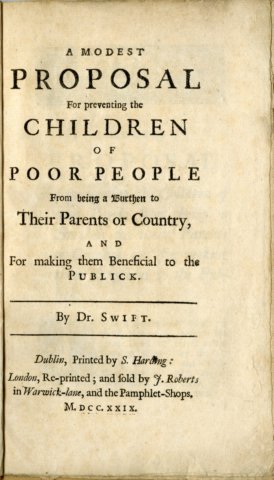

Jonathan Swift, Irish by parentage but Englishman by citizenship, wrote A Modest Proposal in 1729. During the time he wrote this, there was great suffering in Ireland, and the English seemed to be at a loss as to how to deal with that problem. As the name might suggest, Swift hoped that his readers would be convicted to respond to the plight in Ireland by considering his “modest” proposal. Though he is possibly best known for his novel Gulliver’s Travel’s, Swift was at his best when he was writing satire, and that is what A Modest Proposal is: satire. Those who first read this piece probably did not think this “proposal” was satire at first. Their assumptions may have been based on many things, including the somewhat misleading subtitle and the fact that something really did need to be done in Ireland. Although what Swift wrote was for a specific time and place, his message still applied 100 years afterwards and still applies in the present.

As was true during most of the time Ireland was under British rule, Swift’s time saw a great oppression of the Irish people. It is not as though the people were intentionally abused, but their suffering was there nonetheless. They were poor, dirty laborers. Many of the imports to England came from Ireland, while the Irish starved. In general, the Irish were treated as the lessor of society. Because of their great suffering, the Irish often sold themselves to various shipmasters, traders, and colonists so that they might leave their wretched land and eat. Selling themselves for work, often to pay for their passage, was the only way for most of them to find prosperity and freedom because they had no money.

Swift saw the plight in Ireland and the apathy in Britain. Therefore, he wrote his proposal in hopes of waking up the British to the reality they were ignoring. There were many problems in Ireland that the English saw. For one, the Irish had far too many children, who were a “grievance” to society and their parents. They were beggars, thieves. They even demanded the charity of England, who took most of their goods through trade. Moreover, they were Catholic, leading in part to the great number. Swift also notes some of the horrid practices among these people who, as it was well know, were dying and rotting before them in filth, misery, and starvation. Swift writes,

There is likewise another great advantage in my scheme, that it will prevent those voluntary abortions, and that horrid practice of women murdering their bastard children, alas, too frequent among us, sacrificing the poor innocent babes, I doubt, more to avoid the expense than the shame, which would move tears and pity in the most savage and inhuman beast.

This was a great grievance, and the English looked down upon the Irish because of it. But the British missed how their deeds were causing the death via starvation of those same children. Indeed, much like the supposed cannibals of Montaigne’s essay, Swift compares the English to a similar inhumanity. But what is Swift’s solution to this great problem? Well, since the English are already devouring the Irish by devouring their only supply of food, already withholding the support that Ireland needed, already treating them as livestock, Swift proposes that they eat them.

Yes, literally. Or figuratively. His proposal is straight-faced satire, and Swift does in fact go through the many ways a person could eat a child. You can fillet them, roast them, boil them, and, to make sure that nothing is wasted of so plentiful a crop, use their skin for gloves and boots. Indeed, the mothers and fathers would care so much for their children if they could make even three pounds per child. Even a few shillings would give them enough for bread! And then, since they will not have to care for their children after about a year, which before they would have had to raise the babe to adulthood – what an expense! – they can have more children which they can sell for money. The meat will be good and nourishing and the land better able to support others because of their sacrifice. Even if the meat cannot last long, Swift writes, he is sure that there is a “county which would be glad to eat up a whole nation” before it went bad.

By using the workers for food, the tenants of the land could have food to give to their lords, “as they have already devoured most of the parents, [they] seem to have the best title to the children,” like one would treat a mare or sow and their offspring. Some will have to be kept for breeding, but all of the extra people can be slaughtered without hindrance. After all, Swift writes, they are going to die of old age, disease, accident, or starvation anyway. And there really were, he reminds, too many Papists. Why not make the best use of them for the whole country, not to mention those poor starving, struggling parents? This will then support the parents and the country. As his proposal is “of no expense and little trouble,” he can see no reason why anyone would object to it.

Now Jonathan Swift was not actually saying that the English should eat the Irish. Rather, he was pointing out the problem with England’s apathy towards the plight in Ireland. They saw Ireland as a means for trade and supply. Ireland was better off forgotten until they needed it for food, like corn, wheat, or potatoes. The land and its people were not good for much else. Swift is merely pointing out that if the English are so calloused that they are willing to let the Irish starve so that the citizens that live in England may live, then they might as well go the whole way and literally eat the people themselves. They already were being devoured.

Swift’s writing seemed to have fallen on deaf ears, for a similar problem arose during the Victorian Era. During this time, a great famine broke out, and, like before, England basically ignored it or came up with excuses: they are lazy; much nutrition can come from other common plants; we cannot let them become dependent; what would happen if our citizens found out we were financially supporting the Irish?; and so on. In their eyes, the Irish were the unwashed masses, not really citizens of England. They were those who practiced Catholicism and brought this upon themselves by having too many children. They did not really deserve the help of England.

In short, many were practicing ideas that had long since been growing in popularity. These ideas were first plainly written by men such as Thomas Malthus. In his book Principles of Population, he stated that it was good for the masses, the lessor of society, to die out so that, plainly speaking, the strong could survive. If the land could not produce enough to support the people, they would naturally select themselves to reduce the population.

Many different groups of people were viewed this way – from Africans to the Irish. In fact, only a handful of years after the Famine had basically ended, Darwin wrote his infamous book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Not many know the full title of his book, but he meant what he said. Many during Darwin’s time felt the need for the lessor races to die out so that the higher races might live on and not be burdened by those below.

The above image comes from a book called Ireland from One or Two Neglected Points of View written by H. Strickland Constable. The point of this drawing was to show that the Irish are actually descended from Africans, thus making them less human than Europeans. This idea is false on two counts: first, while the Irish and Africans are brothers in the sense that they descend from Noah’s sons, they are not related in the way that Strictland, or others, proposed; second, their origin of descent does not make them more or less human as all are of one blood and are children of Adam formed in the image of God. We may think it barbaric that brothers would treat each other this way, but we are not far from this reality in our own society today.

This was both the main problem and the mainline idea that permeated societies of that time: different races existed and those different races were more or less human. Because of this, millions were oppressed and killed. And while the Irish, among others, were killed for the sake of convenience and apathy among the British, today such an apathy and desire to murder for convenience happens with abortion. Do we really think this practice is any different from England’s? Do we not devour the children? Do we not see them as animals, not quite human, merely a burden to us and society? And if we do not think this, do we not hear it? Do we not find ways to excuse their deaths and encourage their mothers to lead them to the slaughterhouse? Thousands die each day via abortion, yet many people do not care, do not know what it is, or desire it. While the culture is changing, it is not happening quickly enough. Many more will die to the hand of convenience before this horrendous atrocity ends.

Whether people wish to admit it or not, the genocides that have happened around the world – African, European, or otherwise – all of them are committed because of ideas purported by Malthus and his followers, like Darwin, Galton, Sanger, and others. People are killed for difference, hate, and convenience. They are killed because at one point in time, after years of whispers, men finally began to say what they desired to be true, that it was not only natural, but good for certain people to be eliminated, or left to die, for the sake or progress and convenience. And as Swift wrote, we have propped up these people as if they were the “preserver of the nation” despite the fact that they are among those who aided in its destruction. Do we really think we are any different from the British in the way they viewed their subjects as our nation treats abortion? So I ask you: will we look on in horror at our current state, as we do at Swift’s modest proposal, or will we continue to be those who future generations will look on with disgust?

Blessings to you and yours,

~Rose